The Villainization of Aunties: judgemental south asian aunties are milfs, gossiping is praxis in building community, and who truly is the victim?

not justification but perspective: gossip kills but it also saves lives.

I was walking down the street when I suddenly bumped into an old friend. We both screamed in the streets, ecstatic as we haven’t seen each other in years.

“Ohmygodohmygod! HOW ARE YOU?”

Long rambles spilled out of us as we unraveled our lives in the middle of the street. I began to tell her about every minor inconvenience that happened since I last saw her and she naturally did the same.

While we continued squealing, an auntie passed by and glanced over at us, as they usually do. My friend immediately stops talking and leans in closer, grumbling under her breath,

“Let’s go somewhere more private. I don’t want no judgemental bitchy auntie eavesdropping on us.”

She continued talking but as we both went our separate ways, I couldn’t help but think about what she said. Judgemental bitchy auntie. For some reason, those words didn’t sit well with me. But at the same time, I found myself also agreeing. I brushed it off, unsettling feelings withering away as the day went on. If she said the same comment months earlier, I probably would’ve shared the same sentiment. But that day, I wasn’t so sure.

The next day, my mom and I went to a family friend’s picnic in Queens. I wondered if I could weasel my way out of it with a lame excuse as binge-watching Jane The Virgin for the millionth time seemed like a much better way to spend my Saturday.

Ma, my stomach hurts. Ma, I have so much work to catch up on. Ma, I have plans. Ma, I have to save the world from getting hit by a galactic meteorite.

I tried explaining to my mom how I just didn’t want my day being subjected to aunties judging me. I stared at the reflection of my mirror, my stomach gorging out of my salwar kameez and my acne under my caked makeup, suddenly feeling like a court jester to entertain the aunties. But alas, I decided to go, begrudgingly.

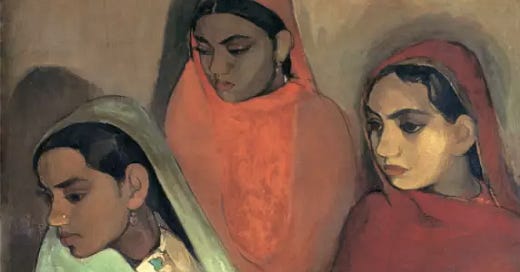

We arrived and found myself hours later not wanting to go home. Us women, a variety of all ages, sat comfortably on picnic blankets under trees. I sat quietly, listening to aunties I knew from afar open up about their immigration journey, how they too were judged by others and even were vulnerable in sharing their mental health issues. I consumed everything that was told that day as their words were soaked with wisdom. Quietly observing Each time they took a shaky breath and sipped on their chai from styrofoam cups when their throat got dry. I keenly listened to the women with loud cackles as it seemed as though they were waiting to talk their entire life and even the shy ones whose gentle giggles hid behind their palms. The day was filled with their vibrancy and I felt taken by it.

But most of all, I quietly listened to my mother who I’ve come to see another side of her. A side that is not necessarily my mother, but rather a woman. Her true essence was hidden inside under the layers of motherly nurturing. I wonder if she hid it purposely. Or did the layers somehow take their form without her even noticing, suffocating her spirit as the years passed? I wonder.

Over time, I noticed that she forgot I was by her side, making raunchy jokes and opening up about her pain when her brothers died. As the day went on, I too felt her being surprised at herself as her eyes shifted every time she said something, suddenly looking over at me with a sense of shame. I could hear her thoughts from across the picnic blanket, “My child is here. I shouldn’t act like this. I’m a mother. Get it together.” But then she heard a funny joke and surrendered.

As I watched her, I felt myself stir with emotions from sadness knowing she couldn’t let herself be like this with me. Then overwhelming guilt kicked in wondering if perhaps somewhere along the way, she lost this part of herself when motherhood took over. But as the day went on and I watched her giggle and run from one auntie to another like a child at a playground, a sense of pride and admiration washed over.

We ended the day by having an elderly auntie, who was an ayurvedic and homeopathy instructor back in Bangladesh, lead a meditation session. She sat on a chair looking down at us as all of us sat on a picnic blanket. We did everything from breathing techniques to even laughing therapy where we all shamelessly manically laughed together in unison as strangers at the park staring at us from afar. A group of Bangladeshi women draped with shiny and glimmery sarees on a hot summer day, howling. But we didn’t have a care in the world. Because we were doing it together.

We drove back home, laughter continued in the tiny car as we sped through highways. When I got home, I slept with the echoes of their laughter and stories running through me.

Over the course of the next few days, I’ve thought extensively about why I felt so uncomfortable going to the family gathering. After years of passive comments, I’ve grown accustomed to recoiling when I saw an auntie, a natural instinct to run and hide. As if an alarm went off inside my body notifying me that I was no longer safe.

Thoughts swarmed in my mind of past conversations my friends and I had about our sadness being brown girls, the oppressive surveillance we are forced under, and how gossiping in our communities is destroying us. But soon, I finally understood how the conversation never went above that. Instead, the discussion pertaining to judgemental aunties and gossip has morphed into something far beyond its origin. While it is rightly justified to discuss the tyrannical hardships the younger generation of brown women has to face, I’ve come to realize that this topic has come to transmute into more harmful complexities. Ultimately, we have encouraged the villainization of aunties and even formed caricatures.

Aunties are now depicted with bindis as big as their forehead stamped between their eyes, thick black kajol smeared across their eyelids over their blue ashy eyeshadow, vibrant fuschia paint lined tightly around their pursed lips, protruding belly tucked under their sarees, a nod to fatphobia.

South Asian Millenials and Gen-Z creators even made millions off of creating their brands depicting aunties as villains. A walking villain looming over innocent brown girls. Us, young brown girls, vs. them, brown aunties. It now exists as a niche subgenre.

The word “auntie” itself weighs a label. It is not simply the definition of an older neighbor or a family friend. It carries heavy negative connotations of a nagging, nosy, and bothersome woman, waiting at every corner to infiltrate our lives. There is no room made to view aunties as people with depth and intricacies. As if because they are women decades older than us, there is no willingness to see them as multitudes. We refuse to see them as a woman with a past, a present, and a future. A woman with conflicting feelings, dead dreams, erotic pleasures, small delights, unrequited love, unfulfilled yearning, and more and more and more. But instead, a one-dimensional person who exists to destroy us and nothing more. The over-generalization of aunties itself is harmful as it instigates the grouping of aunties vs. Millenial/Gen-Z brown women which ultimately furthers division within our community.

However, that is to say, there is truth to the villainization of aunties and the justification is valid (albeit surfaced level as we refuse to recognize its nuanced layers and dig deeper). We cannot ignore the obvious hierarchy and power play that exists. One can also say that it is the aunties’ doing of disrupting unity within the community. Because how can the younger generation stand in solidarity with aunties if we are in constant fear?

Hierarchy within the community prevails as aunties hold power over brown girls by putting us under surveillance, their lethal tongues acting as a violent weapon that can ruin a girl’s life in seconds. Reputation is the shred of existence for women. One’s reputation itself is autonomy, and therefore power even if it is minimal. So when an auntie ruins her reputation, it means snatching away her potential, imprisoning her, and banishing her entire nuclear family from the rest of the community. Because of course, a girl is not her own, she is an extension of her family. If she falls, so does the rest of the family. Gossiping is never just an explosive attack on the individual but burns everyone around them.

Gossiping usually erupts when a girl does something that is against our traditions, which means it was reprehensible. The gossip itself is a way to shame us and restrain us from straying away from our culture and feminity. When our elders warns us about not “slipping up” so people wouldn’t talk about us, it uses gossip as a fear-mongering tool to keep us in check. To maintain modesty and uphold archaic perceptions of what it means to be a “good South Asian woman” living in the cauldron of sin that is western society.

But when examining who exactly is “keeping us in check” and invented the notable rules of “feminine modesty”, it is not the aunties that created the agenda, but the uncles. Uncles have always been the ones that surveillenced us, but somewhere along the way, aunties have become messangers. Are they just as misogynistic as uncles in our community? Or are they also victims of the surveillance that they too have become the surveillancer? It is easy to slander aunties as scapegoats of judgment and gossip when uncles also play a role in this. In fact, they invented it.

Gossip is a way aunties uphold their power in our communities, instigating direct harm. I wonder, do aunties gain gratification from policing younger brown women? Or is it deeper than that?

While violence is perpetrated by aunties through the act of gossiping and judgment, I believe it is important to examine the complex layers of gossiping. It is already given that gossiping kills. But what if it also helps to live? To survive?

Whether we like to admit it or not, everyone gossips and makes judgments. The embarrassing truth is that we all secretly enjoy doing it. From bonding with a mutual on Twitter being haters or hearing how a girl in our neighborhood has 2 boyfriends, or even loathing a rando with our bestie. Many of my friendships started by finding out that both of us disliked the same person. This seems awful when admitted out loud, but nothing ties people more together than prying and sharing the latest news to escape our own lives.

According to NPR, “The origins of gossip can be traced at multiple levels: evolutionary, cultural and developmental. While some forms of gossip are almost certainly negative or superfluous, others seem to serve a beneficial social role: Gossip can help solidify personal relationships and encourage cooperation.”

Gossiping continues human evolution but it also has become a vital way in forming community. A necessary linguistic act in maintaining human connection. It has always been a tool to fit in and find common ground. Needless to say, while everyone does gossip, it is what we choose to do with the gossip that depicts if it’s simply a harmless conversation or our intention to inflict harm.

I think about South Asian aunties that immigrated to America with nothing and had to start their lives from scratch. As most of the aunties in the Bangladeshi community immigrated to America during the ’90s or early 2000s, they had no accessibility to long-distance phone calls as we have now which meant being forced to cut ties with friends and family they’ve known their entire lives, thus erasing the only community they knew. Along with restarting their lives in a strange new country with a culture that plays a juxtaposition to theirs, they also had to find community and allies.

As they immigrated to a new country, now existing under the realm of white supremacist capitalism post 9/11, the only way they knew how to survive was by adapting and succumbing to a wolf pack mindset. Survival of the fittest. Similarly to people I know and including myself, they too found common ground with other aunties by expressing their dislike of others in the community. I imagine aunties that arrived in America, an unfamiliar nation with unusual customs, analyzing the land around them. Alas, a survival tactic available to them that they can cling onto: gossiping. While I am not saying it is justified and that gossiping is the only way to survive, I think of how oftentimes we project harm when surviving. Is there a “right” or “wrong” way to survive? I suppose there aren’t many options when it comes to our survivalhood.

And so, is gossiping and judging simply a power trip for aunties? Or is their own flawed way of taking back control in a country they’re victims in? Perhaps all of these things can coexist together.

I think back to the villainization of aunties and my friend’s words “judgemental bitchy auntie”. While slandering aunties feels shallow and warrants harm, I wonder if maybe this is our own way of trying to take back control and fight back. Are we all, the younger generation of South Asian women and aunties, just trying to scavenge crumbles of control? To reclaim the little autonomy we all have? Even if it’s through harm?

When examining the oppressive role aunties leans into and who ends up being the victim of gossiping, we would immediately assume it would be someone that is part of the younger generation of brown women (millenials and gen-z). But we often forget how fellow aunties, that are oftentimes also in the age group of the said judgemental aunties, are also victims of gossip as well.

A couple of days ago, I met with a close friend about my thoughts. To my surprise, she responded by talking about how her mother doesn’t really have a social life, and when she does go out for pleasure, it is usually a family outing.

“Actually…I don’t think she has any friends. I think she’s scared of being judged,” she said. “Judged by other aunties.”

The caricature we built of the “judgemental bitchy auntie” made us forget about aunties like my friend’s mother. Many of the aunties in our communities are housewives, their proximity to society or the outside world are through their husband and children. I thought of my friend’s mother, who I haven’t had much conversation with besides “how are you”. How like so many others, she too refused to leave the house out of fear and judgment. Ultimately living in isolation from racist America that ignores them and alienation from other aunties.

The judgment between aunties also holds vast complexities. From geographic elitism (aunties that grew up in middle-class cities vs. aunties that grew up in poverty in rural villages), classism, colorism (because aunties are also victims of colorism too), casteism, and so much more.

It is easier to believe that it is us, the younger generation of brown girls, against “judgemental aunties”, but the truth is that the ratio between the gossiping aunties and aunties that hide at home out of fear of them is damning. But even then, there still lies complexities within the ratio itself. Complexities that go deeper into the ocean.

The only time we think of the aunties (vulnerable helpless housewives, perhaps another character we developed) that exist as shadows of our world is when we garner academic conversation of intersectional feminism, and neoliberal representation, and to prove that we support “all women”. But it is tragic to see how the language suddenly shifts from “auntie” to “immigrant women” when we wish to. How it is “immigrant women” when talking to our white counterparts or angry Instagram rants about equality but suddenly “auntie” when we desire to slander them.

Perhaps this goes to show the wavering truth aunties hold. From being a victimized minority in white America to a daunting bully to a wife and mother with dead fantasies. All of these things breathing together simultaneously.

While aunties in our community have power over the younger generation through surveillance, it is important to take a step back by expanding the scale and analyze this said power. Largening scale from the 5-block width of our neighborhood to American society as a whole. The truth is, the young generation of brown women has the ability to step into an entirely new world by simply getting on a train to a new neighborhood while aunties are not able to.

In our workplace, college, even restaurants in the city, and more, we have the privldege of being part of the greater American society and engaging in multiple communities. We are able to temporarily escape being subjected to their judgment. Many of us will move away from the communities we grew up in, making the escape permanent.

However, the aunties we grew up with cannot. Between the unfamiliar culture of western society and its blaring differences to language efficiency, they cannot afford to escape their neighborhood, no matter how small it may seem in comparison to the rest of the world. The community is their world. So, in some way, do we have power over them? The power being our proximity to Americanness?

Frankly speaking, the chastisement between aunties can be far worse than the torment the younger generation faces, as isolation can be just as violent. However, it also begs the question if one can measure harm. Who loses the most when it comes to gossip culture and judgment? Who hurts more? Who harms more?

I do not have all the answers to these interrogations, and I’m sure neither do our aunties.

But I pose the question, who is truly the victim? Who is the villain? Us? Or them?

Perhaps I can start the conversation by asking aunties how their day was. What their dead dreams are, what do they find delights in the smallness of things, have they experienced unrequited love, their unfulfilled yearning, and more and more and more? Maybe I will find the answers then. Or maybe not. But maybe then we can understand each other.

The conversation will continue to unravel and spiral. As it is bigger than all of us.

If you liked what you read and/or learned a new perspective, consider sending me a tip!

Venmo: fablihayanbar

Paypal: fablihanbar@gmail.com

<3

thank you for verbalizing this. i have thought about this a lot in the last year, especially about how the villainization of aunties is often tied to fatphobia because south asian communities have really inappropriate discussions about body image in both directions. i appreciate you sharing the discomfort you felt in conversation with other young south asians, because i’ve definitely felt a lot of the same

stunning piece. i went for a swim with my grandmother and her friends once and it (the act of being together + gossiping as exchanging news) changed the way i saw older women in my community. they're just like us! we'll grow old and become them so very soon! we are all aunties!!!